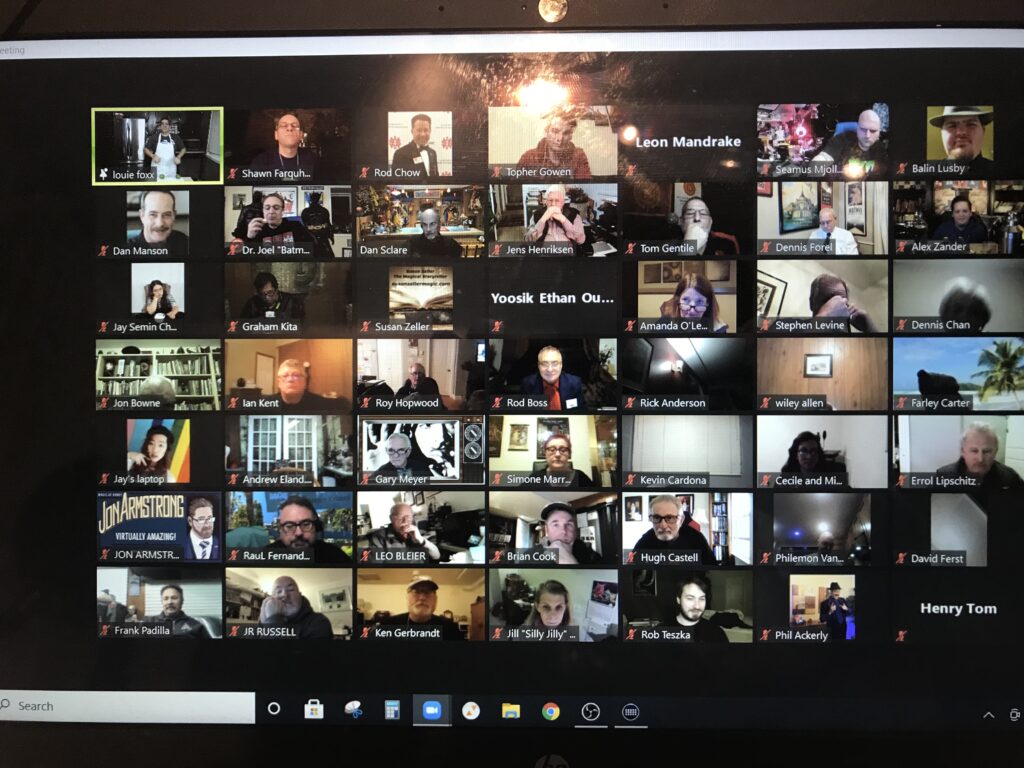

Magicians and audiences from Boston and around the world gathered together virtually for the Boston Magic Lab’s final show of 2020. With backdrops varying from simple bedrooms and offices to more elaborate studio setups, six performers presented the audience with impossible effects ranging from a perfect prediction of a spectator’s thoughts to a chosen playing card emerging from a jar of vegemite. In the show’s unique digital format, viewers spammed “1”s into the chat in lieu of applause, and volunteers were toggled from viewers to panelists when they interacted with the performers.

Now a year old, the Boston Magic Lab is one of the latest additions to the Boston arts scene. The group hosts a monthly open-mic for magicians to test out new material. The show is entirely free for audiences, who are instead encouraged to contribute to local charitable organizations. The magicians aren’t paid to perform — rather, they receive in-depth feedback for their routines.

The Boston Magic Lab was founded by Felice T. Ling, a social anthropologist and street magician who is a regular performer at Faneuil Hall. After having a chance to test some new cabaret material at the Toronto Magic Company, she was inspired. A few years later, Ling’s magician friends from Toronto visited Boston, and they sent out a call for local magicians to come hang out. It was then that Ling met many of the magicians who would join the Boston Magic Lab crew. “[I] realized that there’s a lot of little tribes of magicians in the area who were also craving the same thing that I was looking for,” Ling said, “which was community and a place to perform and try out new stuff.”

While open mics exist in stand-up comedy, the concept of a magic open mic is a relatively new idea. “I think part of the challenge of magic is a lot of people do it as a hobby, which is great, but then it’s always tough to find places to perform live, where you can test new material and you can be, quote unquote, you can be bad to get better,” said magician Adrian Saw, an Australian financial trader based in Singapore who has performed magic in comedy clubs throughout Asia. An open mic platform gives new magicians an opportunity to practice and seasoned professionals a chance to take risks.

One of Ling’s goals for the organization is to spotlight local magicians. In pre-pandemic times, the Boston Magic Lab was housed in the Rozzie Square Theater. “Feeling like Boston is very important to us,” said Ling. “The goal is still to try and keep three slots for Boston area or New England area magicians.” Another of Ling’s goals is to showcase marginalized peoples. “There are so few magicians who aren’t white men, just to be blunt,” she said. “I think [representation]’s really important because for me, the first time I saw a magician on stage who looked kind of like me, that was huge.”

Like all the performing arts, magic has been struck a terrible blow by the pandemic and the subsequent closure of nearly all in-person venues. Magic carries a physicality that is distinctly lost in this virtual world. Viewing tricks through a screen is a significant change in the experience, not just for audiences, but for the magicians themselves.

“If I, for example, turned a coin into a solid steel ball, you just have to believe that what you’re seeing is a solid steel ball, you can’t actually feel it. You can’t actually see that this is a solid steel ball, no longer a coin, and that’s the most difficult part, because everything is visual, is no longer tangible,” said Jay S. Chun, an Edmonton based street performer known for her circus skills. “And as a street performer who works with a lot of, ‘Come close, feel my props, these are regular props, let’s do magic with them,’ is entirely out the window.”

Similar to stand-up comedy, magic relies heavily on feeding off of an audience’s energy — interpreting reactions and altering one’s performance in real time to create a unique and engaging show. Performing for a screen is very different from performing on the street, in a club, or on a stage. “For me, what this is is just a great big game of pretend,” said Benjamin L. Barnes, the current Entertainment Director at the Chicago Magic Lounge. “I am imagining what [people in the audience] look like, I am imagining that they’re having fun and so I’m having fun with them, never seeing them. It’s all just make believe. And I imagine things are going great … There was one point in the show where I said to everyone, ‘I can see some of you are clapping, thank you so much.’ I saw none of that, it’s just in my imagination.”

A virtual format does come with some benefits. “It’s been some of the most creative times of my life because I’m able to pursue stuff that I wouldn’t normally do,” said Louie M. Foxx, a Seattle based magician and two-time Guinness World Record holder, who has been experimenting with creating short pieces of pre recorded content.ADVERTISEMENT

Saw agreed, referencing a trick he did with a coin during the recent Boston Magic Lab performance — something that would usually be considered close-up magic. “I couldn’t really do that in a live environment, in a stand-up or comedy room because no one past the first row could see that coin, but in a Zoom environment where you’ve got the camera right there and the audience can see a tight frame, you can start using different things that you wouldn’t otherwise use in a live show.”

For now, virtual shows are the only option for most magicians. All of the Boston Magic Lab performers emphasized the importance of pivoting and taking advantage of this new opportunity. “Every single platform: TV magic, close-up magic, parlor, stage, they each have their own beauty to it, and you just have to try to find that beauty in every single one,” said Linda Hung, a recent graduate of Pace University currently based in NYC. “And virtual shows [are] just a new platform that people need to find the beauty [in].”

Barnes said that, if anything, magicians will be better performers after working in the virtual realm. “I think this situation has forced us to learn to connect with people more because of the obstacles of not being there with them physically … If you can connect with people through a camera, that’s a great skill to have.”

For the Boston Magic Lab, moving beyond physical space means reaching a larger circle of magicians. “I think switching online has helped me find people in the New England area, actually, that I did not know of here,” said Ling.

The performing arts scene is bound to emerge from the pandemic as a changed industry. Much of in-person magic involves working with volunteers, passing around props, and choosing cards, but in a post-pandemic world concerned about hygiene, this is unlikely to come back any time soon. All of the performers agreed that the virtual magic show is here to stay, even after a return to in-person venues is possible. “It’s inexpensive, you can connect people in different geographic locations, and it’s a lot of fun, and I don’t think it’s going to go away just because we can be together in person again … honestly, I think it’s good. It’s another avenue through which magicians can make a living, which is fantastic,” Barnes said.

Audiences may be Zoom-fatigued, but there are still reasons to seek out virtual magic shows, even more so than other virtual entertainment. “[In] most of those other art forms it’s a fixed performance and an audience member would see that same show if they watched that virtual performance five times,”Saw said. “But in a magic show, you’re going to have audience members making different decisions … I think people have been so isolated that just sitting, watching passively a Zoom show is not really what people want in this kind of environment — they want to be involved. They want to have their camera on. They want to talk, they want to make decisions, and I would say magic is probably one of the only art forms in a virtual medium where people can do that.”

As for the Boston Magic Lab, they intend to resume performances in January 2021 after a two-month hiatus, during which they plan to rework and improve their show and continue to build an unpretentious and inclusive community.

We’re not a nonprofit, we’re not an official organization,” said Ling. “We’re just a group of friends who want to put together a good show.”

By Sam F. Dvorak, Contributing Writer